46 in (116.8 cm) high, 23 in (58.4 cm) wide

cf. Carol M. Osborne, Venetian Glass of the 1890s: Salviati at Stanford University

Gabriel, Hanisee Jeanette, The Gilbert Collection: Micromosaics

Liefkes, 'Antonio Salviati and the nineteenth-century renaissance of Venetian glass' in Burlington Magazine, May 1994, p. 285

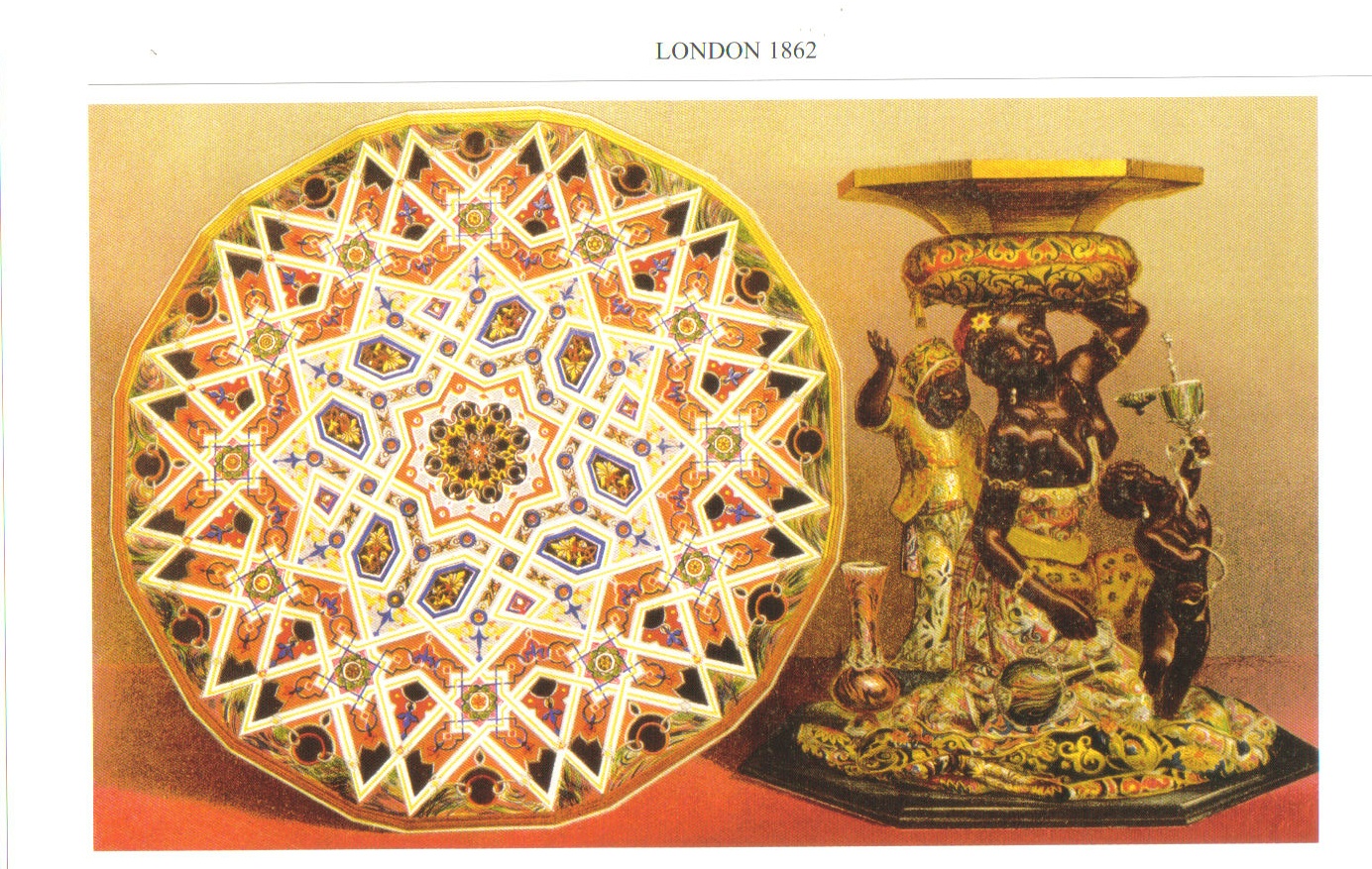

Jonathan Meyer, Great Exhibitions: London, New York, Paris, Philadelphia 1851-1900, 2006, p.144, fig. D67

J.B. Waring, Masterpieces of Industrial Art and Sculpture 1862, plate 280

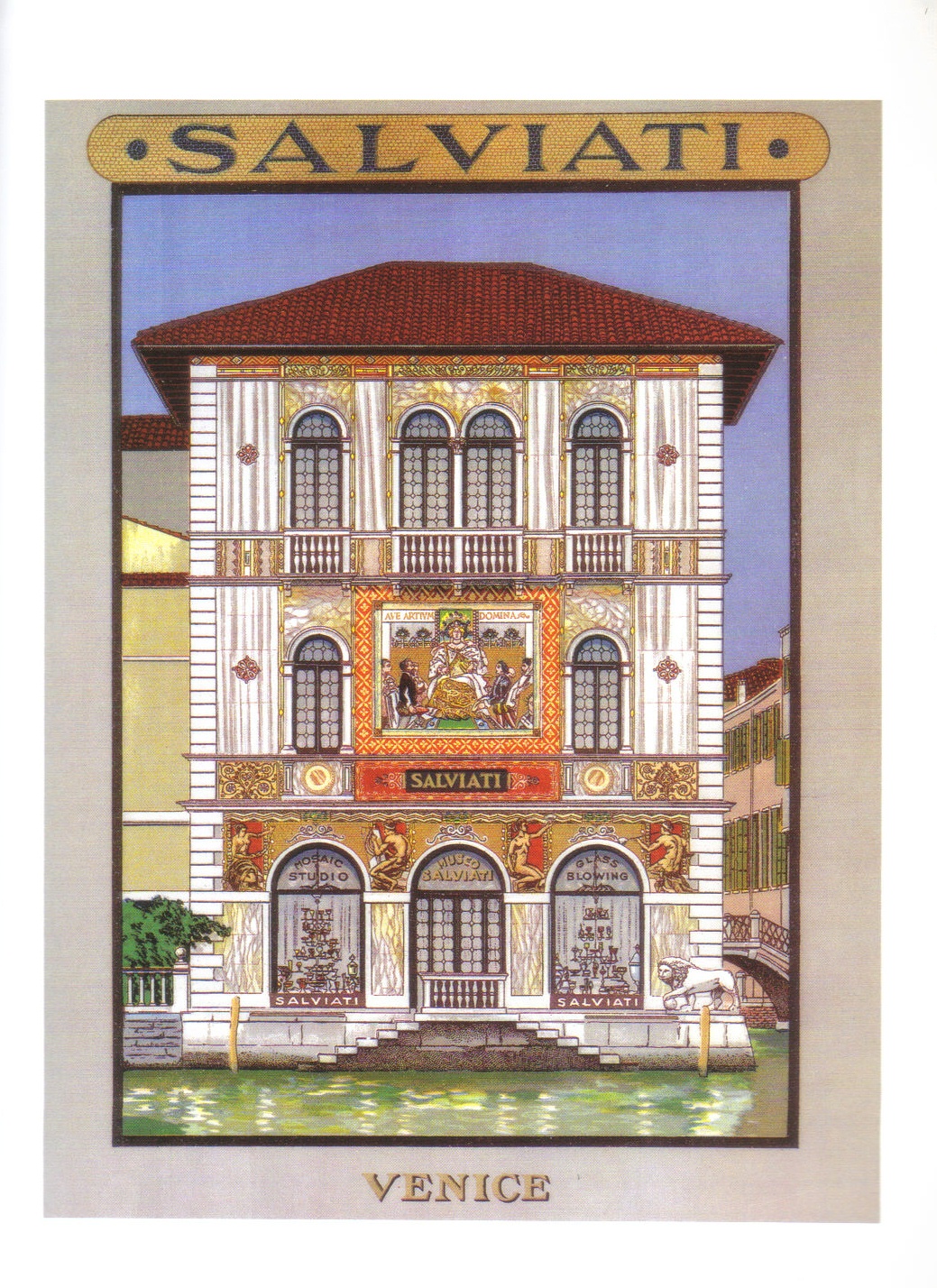

From the 1830s, however, the 19th century saw a renaissance in the Venetian glass industry. Among the many glass companies involved in this movement, Antonio Salviati’s was perhaps the most successful at gaining international recognition and commercial success. Antonio Salviati (1816-90) was born in Vincenza and started his career as a lawyer. In the 1850s, however, he worked with the glassblower Lorenzo Radi on the restoration of the San Marco mosaics. He quickly became fascinated by the technique and in 1858, he began making mosaic and vessel glass himself. In 1859, he and Radi opened a glassmaking company together, and quickly gained international acclaim at expositions in 1861, 1862, and 1863.

In 1864, partly through the initiative of Salviati, the First Glass Exhibition was held in Murano, repeated the following year in Vienna, where Salviati presented works of monumental and ornamental mosaic. From then on for many decades, the manufactory was a constant presence at all the principal exhibitions, both national and international, winning no less than ten prizes in just a few years: in Paris in 1867; Venice in 1868; Murano in 1869; Rome and London in 1870 and Naples, Milan, Turin, Vienna and Trieste in 1871.

The firm’s success, especially in England, was so immediate and vast that in 1866 Antonio Salviati entered into partnership with some English investors including the diplomat and archaeologist, Austen Henry Layard and the antiquarian, Sir William Drake. They renamed the firm, The Venice and Murano Glass and Mosaics Company Ltd. However, divergences with his English partners progressively increased, and in 1877 Salviati split from them and set up two separate firms: Salviati e C., specialised in mosaic, and Salviati Dott. Antonio for blown glass.

The company Salviati & C. became known not simply as a manufacturer of glass vessels and mosaics, but also for its experiments and development of technique. Layard was interested in Roman and pre-Roman glass techniques, such as murrine, and Salviati’s mosaics became popular not only in Europe, but also America after he presented a mosaic portrait of Abraham Lincoln as a gift to the United States (it now hangs in the Senate House in Washington, DC). Such was the popularity of his work that American tourists in Venice would bring back pieces as souvenirs, despite the fact that it was already available in America: Tiffany & Co stocked Salviati’s wares at their 5th Avenue location in New York.

Already in the early 1870s the activity of the Salviati manufactory in the field of architectural mosaic decorations became intensive and internationally renowned, contributing with its technical excellence to the revival of this ancient art in the last years of the 19th century. The mosaic works produced in these years by Salviati include some prestigious commissions in England: St Paul’s Cathedral, the Royal Chapel of Windsor Castle, the lobby of the Houses of Parliament, as well as the works for the Palace of the viceroy of Egypt and in the Castle of Marienburg in Prussia.

When he died in 1890, Antonio Salviati was succeeded by his sons Giulio and Silvio. Silvio’s prerogative was mosaic; in 1903, together with one of his father’s former collaborators, Maurizio Camerino, he founded the Erede Dott. Antonio Salviati & C. which continued activity under this name up to 1920. Meanwhile, the activity of the other company, Salviati & C, set up in 1877, continued. It still exists today.

Even after the demise of the founder, the Salviati firm continued to reap success in the field of mosaic decoration, both in Italy and abroad. A particularly important commission was for the church and buildings of Stanford University at Palo Alto, in California, the mosaics created in the last decade of the century to cartoons by the Venetian painter Antonio Ermolao Paoletti (1834-1912). This was not the only occasion of liaison between the Salviati firm and the vibrant and accomplished work of this artist who specialised in subjects of contemporary Venetian life, and in the 1890s, if not earlier, their collaboration blossomed into a permanent partnership.

It is quite probable, therefore, that the panel showing the Woman in kimono derives from a pictorial model by Paoletti, in whose paintings we can observe a similar kind of florid female beauty in the taste typical of the Belle Epoque, depicted in a style based on crisply drawn and solidly modelled forms. The subject of the panel, together with the elegant frame, are clearly inspired by ‘japonisme’, a style which, from the 1870s to the end of the century, enjoyed a vast and lasting popularity in the figurative and decorative arts.

The number 224, legible on the rear of the panel, can plausibly be interpreted as an inventory number connected with one of the numerous Exhibitions in which the Salviati manufactory took part; these are almost always impossible to reconstruct accurately since complete catalogues of the works on show were compiled only rarely.